I persuaded James, our marine science officer, to sit down and talk with me about the building of our artificial coral reefs. Turns out I knew nothing about coral and how fascinating this industrious animal is. Thank you James for blowing my mind!

- Why are we building an artificial reef here?

Because we want to see if, firstly, it works as a viable way of restoring biodiversity and we’re also hoping to be able to use it as a way of working with the President of Ampangorina to make this a protected area of reef.

- So it isn’t protected at the moment?

No, we want to set it up as a protected area, to reduce the fishing and we’re hoping that the artificial reefs will work favourably towards that.

- Do you know that species are diminishing here?

Around here it’s probably more of a pre-emptive strike. We know fish are being affected by the fishing on the reefs – a lot of the larger fish are now missing, but smaller species and coral are still thriving.

- But this has never been done before here?

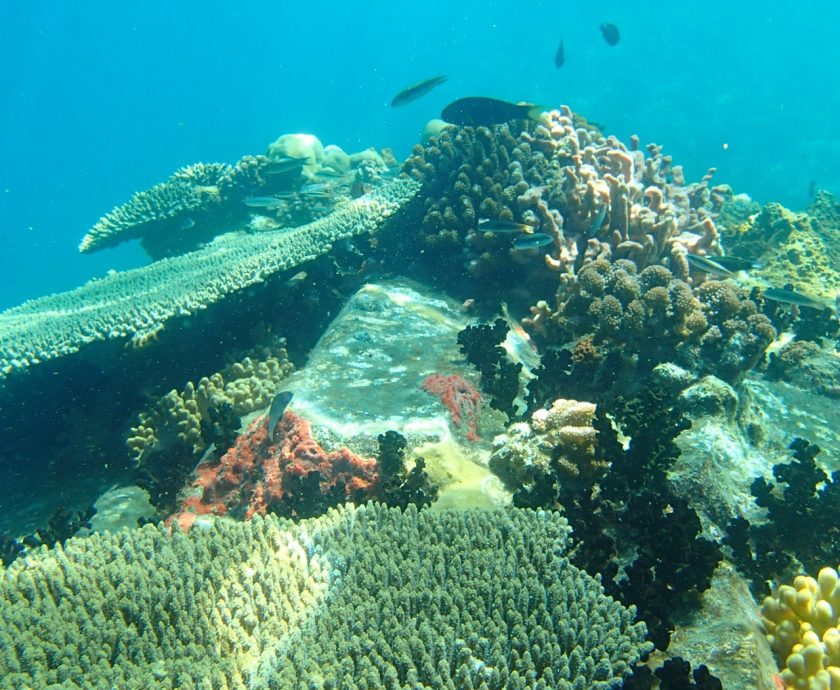

I think over the other side (of the channel) there’s a guy who’s been working with planting coral gardens but he says he is mainly focused on soft corals because he’s found that hard corals struggle, which is why we’re building so many reefs, as a sort of test, to see what type of coral grows best and whether we can promote better conditions by using different techniques and reef structure.

- How many reefs are you building?

At the moment, we’ve got five out there and we want to put another two out. The first three we put out, we put there to test that the building works and that they can withstand the current and now we want to plant four more. So there’s already two out there, we want to put another two in, to have one that’s hard coral, one that’s soft coral, one we’re just going to put rock on and then one we’re going to leave as a metal structure, to see how the eventual growth on the structures differs.

- How do they work – what do you build them out of?

Each reef is a pyramid made out of metal framing which is just four bars with a cement weight holding it all into the ground with squares over the top to give it more of a 3D shape. After all of that has been tied together and made secure we find fragments of coral tips, that’s the newly grown coral.

- Like a sapling?

Yeah, and then we attach that to different parts of the reef to try and encourage it to spread out and grow on to the structure.

- So it doesn’t need anything in order to attach?

Well, that’s the stage we’re at now. From going back to the reefs that we’ve already installed, we’re finding that some of the structures aren’t holding up so well in the current. So we’re going to adapt that and make them a little bit shorter to reduce the impact the current will have and we’ve also found that algae is sort of smothering the structures before coral has had a chance to grow. There are two ways we can go with that – we can either focus on planting Acropora coral on the reefs which is known as a faster growing coral so it may not get smothered as much, or, something we’re looking at, more as a long term solution, is to attach an anode or something that produces a current to run through the metal of the structure which will promote it’s rusting, which, in turn, will give off oxygen which has been proven to promote coral growth and inhibit algae.

- Like an electric fence?

So that’s something that we want to try, but whether we can within our budget, I don’t know.

- Why is coral important?

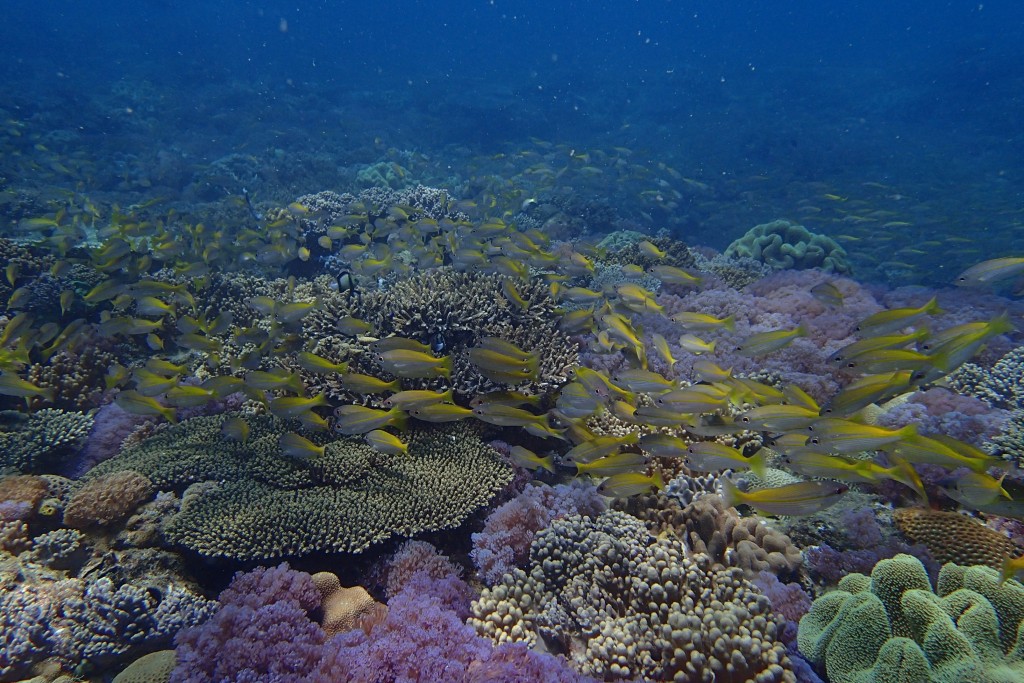

Because it provides the basic platform for everything else. The more diversity in coral you have on a reef the more niches you have for everything else to then fit in.

- Have you seen anything making homes in any of the reefs you’ve put out?

Yeah, they seem to have benefited fish quite quickly! Pretty much each reef has its own resident lionfish (Pterois) which has moved in and they’re already very territorial of their reef if any divers go near it, to fix it or anything, they’re very protective, which is cool.

- Do you usually only get one lionfish per reef because they’re that territorial?

No, some of them seem to be sitting in pairs, and the pairs move around the reef. We’ve had some emperor fish move in (Lethrinidae) – the emperors were primarily found over the sand at the edge of the reef, so these artificial ones, being further off shore than the reef itself, are being used for shelter by the emperor fish and quite recently we’ve seen juvenile fish on the reef too, which shows that fish have been using it for spawning and recruitment which is really cool.

- That is cool. In terms of the materials that you’ve used to make them, is that environmentally sound? To be putting metal and things in the sea, or is it a ‘greater good’/‘means to an end’ sort of thing?

We’ve selected the metal because we know that it’s the ‘done thing’, it’s a proven method, particularly with ships and things like that proving to be effective artificial reefs

- So wrecks are essentially artificial reefs?

Yeah.

- Have they been created around the world? Are they used as a form of regenerating biodiversity and building habitats the world over?

Yeah, so quite close to military naval bases and things like that, they’ll sink a ship when they’re no longer needed in service. 50% of the time that’ll be to create a dive site but more often than not they will sink it with the aim of creating a structure for a reef to grow.

- It’s really cool, using waste as a way of regeneration.

Yeah, I’d really love to be able to sink a boat here.

- Surely reefs won’t grow at any depth. Are certain conditions necessary?

Depending on the location yes, it does largely depend on the conditions. Our reef is maybe 150m out and we’re building ours a further 20m from our current reef, so completely out on the sand.

- So they’re not extensions, they’re brand new reefs?

Yeah.

- Why?

Partly because we didn’t want to interfere with this reef whilst we’re testing it all out and we’re carrying a lot of heavy stuff over the reef which we don’t want to drop but also, it’s thought there’s a protected area at the end of this channel (between camp and Lokobe National Park) and then there’s Tanikeli (marine reserve) at the other end and it’s believed that those protected areas feed everything else, that the current carries all the coral recruits and the fish recruits down through the channel, which is thought to be why we’ve got such nice reefs here. So we’re hoping that by having these reefs out in the channel it increases the chance of them collecting.

- Wow! Like reserve nets. Is it challenging to build them, for you and the volunteers? You mix the cement and build the structure here (in camp) and then do you swim it out in teams?

All the metal can be swum out. Depending on the size of the cement weight that ends up getting built we can either swim it out or use the boat. The only really challenging part is making sure divers are out of the way of heavy objects and sharp edges.

- What would you like to see, in terms of the future of the reefs? What would be the perfect outcome of this experiment?

I think the perfect goal at this stage would be to know that they’re structurally sound. There are some improvements to be made to the ones already out there, but to know that they’re permanent structures and (probably what’s going to be well beyond my time here) to know that there will then be an MRCI built reef!

- Can it be added to over time?

Yes and that’s something which makes it a really great project because we can always have new volunteers building, seeing the reef built from the dry stage and having it up in the water. As long as they’re standing it doesn’t matter how many we put out there, other projects that have done it. Google images of ‘artificial reefs’. They create entire meadows of these things, if they then do eventually take hold and become reefs, that will be an extensive system to which you can continually add.

- So it’s self-perpetuating?

Yeah, because, provided we have the conditions, all the coral requires is a hard substrate to attach onto. A coral can’t start from sand, it needs rock to attach to and then grow from, so these artificial reefs are extending the available substrate.

- How does it stick to something?

I’m not actually sure on that one.

- Is there quite a lot that is still unknown about coral?

I’d say it’s definitely well studied, (although) there is quite a lot not known about reefs. It’s thought that even now there are still millions and millions of species still to be found on reefs.

- Do they all spawn at the same time but nobody knows why – aside from that it’s something to do with the moon?

Yeah, so at some points during the year there is spawning everywhere. It’s not so sudden, but definitely diving now we’re seeing so many more baby fish and juvenile animals. Everyone comes back from their dives saying ‘I saw these tiny tiny fish!’ but previously in the year you’d be lucky if you saw a baby fish so there seems to be a definitive point when suddenly everything gives birth.

- A coral is an animal…

Yes, so each coral that you see out there is a colony of tiny animals. They all live in little cups and when they feed they extend their tentacles out, which is why some coral looks furry, and at the base of the cup the coral polyp, which is the animal, secretes calcium carbonate (limestone) and that allows the colony to grow out. So essentially they’re huge limestone structures built by little tiny animals and multiple colonies form next to each other to create the reef.

- That’s incredible! So does the polyp (the animal) find itself a rock that’s already there and just move in or is it the structure itself, the bowl that it sits in, it’s body, or has it just found the bowl?

This is the part that I’m not completely sure on, I know that a colony will grow as new coral settles on old coral and will either use the original cups or build its own and then grow out from there – I don’t know how the original colony starts.

- How do you know if it’s alive or dead?

Usually dead coral will be taken over by algae, so if it’s covered in algae it’s usually dead but you can tell almost by the colour because most coral will form a symbiosis with an algae which lives in the cells and gives it the colour; when the coral dies the algae either dies or is expelled and moves on so you’re left with a section of a coral – there’s no other way to describe it – looks lifeless. You’ve got the living coral around it and a lifeless rock centre and you can (it’s hard to describe) quickly see.

- When the tide goes down and it’s exposed, is that really bad for it?

Some species, yes. Most coral can’t tolerate direct exposure to sun.

- Is that what coral bleaching is?

Bleaching is when it expels the algae, that can either be a disease that induces the expelling of the algae, or the coral is stressed by changes in temperature and such and it’ll expel the algae so that it’s not having to share resources. It is reversible, unless it’s prolonged. When the tide goes out and we have the reef out, usually here, it’s just Acropora that comes out which is the fast growing coral and specialised to withstand higher light intensities and more waves which is why it grows at the top. But most coral can’t withstand it, which is why most coral reefs stop at about five meters.

- The coral that grows here, is it endemic to this area? Is it rare, or does coral just tend to grow everywhere? Is it more about the fish that it attracts rather than the coral itself?

There are global spacial distributions of coral. There tends to be a few genus, like Acropora, Porites, Montipora, but within that there are lots of different species that will be specific to different regions. I think the regions are larger than just North West Madagascar, so I don’t know about there being much coral endemism to Madagascar.

- Do you want to say anything about coral reefs that I haven’t asked about?

I don’t think so.

- I’m so interested in coral now… it may be my new favourite animal.

I know, it’s crazy. Biological warfare as well, I always found that amazing when I learnt that.

- Then you just drop in ‘biological warfare?!

Okay, I’ll tell you. So coral is really, really competitive with other coral species and what they’ll actually do, quite often you can see, when there’s two directly competing species next to each other you can see a line of no coral between them because they secrete chemicals which poisons the coral next to it.

- Like a no man’s land?

Yeah, but it’s actually really dangerous for reef health because they’ll just secrete this chemical which kills coral in the water that then gets carried by the current somewhere else.

- They’re just killing themselves?

Yeah, but just because they’re so competitive for space with this coral next to them.

- They all just exist alongside each other most of the time. Do you have some reefs that are

taken over by one type of coral?

Not completely, there are corals that are stronger than others. Here we’ve got a lot of Porites, Montipora and Acropora which seem to dominate the vast areas of the reef but it’s a really delicate balance. We get the crown of thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) here which feeds on coral and is really important for reducing the competition of coral to keep that balance. But if the crown of thorns starfish is disturbed it then goes into a population boom and can destroy entire reefs, so it’s a huge balance, which is why it’s so easy to disrupt just by removing one animal or destroying one area of the reef.

- Wow! Can you tell the age of a coral in the same way as counting the rings on a tree?

I don’t know what it looks like, I know that to grow, coral has to take in calcium and carbon and the ocean works as a carbon sink and carbon cycle of the atmosphere. So whatever the carbon levels in the atmosphere, they will be recorded in the sea and taken up by the coral. So you can see levels of carbon and if you can relate those to levels in the atmosphere you can get years that way.

- What’s the general life cycle of a coral, can they get quite old?

Yeah! There are corals out here (gestures to the reef) that are thousands and thousands of years old – well the colony. As the polyps die, the new polyp will grow on top of that so the colonies you’ll see out here could be thousands of years old.

- How do you know?

Just from the size and the knowledge that coral is slow growing. Coral will grow maybe a millimetre out a year. You’ve got huge bommies (stand-alone coral structures) out there which are metres and metres thick and wide. That’s years and years of growth.

- I’m going to have to start diving.

Depending on where the coral grows and the conditions it’s experiencing, it will change it’s growth which in turn further increases the diversity of available habitats for the animals. At the top of the reef you’ve obviously got a lot of wave impact and storm surges, so the corals will favour large robust structures – boulders and pillars – so that they can withstand the waves. Whereas further down the reef, as you go deeper, you’re then not affected by water movement, light becomes the issue, so the same species that are boulders and pillars at the top can be plates and cables and encrusting forms at the bottom to maximise light.

- So they just adapt?

But then, if you’re going out like this (gestures a plate formation) to maximise light in an area prone to high sediment run off from the coast, you’re just going to get smothered. So in areas like that, they then grow in vertical plates and lettuce-like structures to reduce the amount that they get smothered but whilst still maximise their light.

- That’s amazing! What are coral predators?

The crown of thorns starfish, parrotfish (Scaridae) and butterflyfish (Chaetodontidae) – carnivorous fish. Parrotfish, you can always hear them when you’re diving, just scraping at the coral with their beaks and then butterflyfish have little snouts and can reach in and take individual polyps.

- How does a coral defend itself?

Well they’re related to jellyfish (Medusozoa) so they can actually sting.

- Who came first?

Taxonomically it’s all the group Cnidaria, so in the group Cnidaria you’ve got the anemone (Actiniaria), the coral and jellyfish and they’ve all got the stinging nematocyst cells. Some corals will use those and another defence is to retract into their cups.

- So the coral actually just refers to the polyps in the rock structure?

The coral refers to the colony which is the structure and the polyps are the animals.

- So you can’t have an individual coral?

Some species can be identified by their colony shape, so it is made of rock but it’s a very specific structure and shape so the rock is also considered part of the coral species and is important too.

- How are jellyfish and coral related?

It’s to do with their life stage, I don’t 100% remember but Cnidaria go through stages in their lives – the polyp is fixed to the ground and then the Medusozoa stage is when they are free swimming. So anemones and corals are Cnidaria that release their eggs and fertilise in the water and their larvae are at Medusozoa stage and then settle.

It’s to do with their life stage, I don’t 100% remember but Cnidaria go through stages in their lives – the polyp is fixed to the ground and then the Medusozoa stage is when they are free swimming. So anemones and corals are Cnidaria that release their eggs and fertilise in the water and their larvae are at Medusozoa stage and then settle.

- How does a coral mate?

Some corals, mass spawning, will release all their eggs and sperm into the water and just hope it meets and some do cloning, so if a bit breaks off it’ll just land next to it and grow into a new coral.

- It’s like space underwater.

(James nods in agreement).

Thank you to Liz for the beautiful photographs!