Author: Angus Hamilton

The Panthers of Madagascar

When I landed in Nosy Be, an island off the coast of north-western Madagascar, after over a day spent in transit, I could not wait to dive in and get started. Although I was apprehensive about being in a totally different environment to what I was used to, I wanted to be in the forest, finding animals as quickly as possible! Luckily for me, it wasn’t long at all until I got my first look at some of the wildlife of Madagascar.

As we sped towards Hell-ville, the main town and port on Nosy Be, and the boat to my new home for the coming months on Nosy Komba, my eyes were glued to the rich green of the forest that surrounded the roads. A mere five minutes after leaving the airport though, a flash of vibrant green by the side of the road caught my eye. Something hanging from a tree branch. A slender body, but with a large casque (helmet-like structure) on its head, and a white stripe running down the side of its body… it was a male panther Chameleon (Furcifer pardalis), a species I was going to get to know pretty well over my first days at my new home.

The next day, while sitting down for lunch I spotted from the corner of my eye a green shape extending from one of the roofs of the huts. At first glance it seemed to be an overly large leaf, but after paying closer attention I realised that it was actually a male panther chameleon!

He had slowly, methodically made his way down to the edge of the roof trying to make his way to safety: a nearby tree branch. It was a great opportunity to witness some of the unique, and somewhat bizarre, adaptations that chameleons have developed over the years.

Our male (let’s call him Kobi) was precariously dangling from the edge of the roof. His back feet were clamped firmly onto the plant material used to create the roof; his prehensile tail wrapped tightly, acting as an anchor allowing him to reach (for the branch just out of his grasp).

Watching his efforts, the ingenuity of evolution and its work on chameleon feet left me in awe! Incredibly there is no perfect scientific description for their feet! “Wait… what?!” It’s true!! Chameleon feet are bizarrely unique in the animal world. How cool is that?

They fall somewhere between two categories: didactyl and zygodactyl. On the one hand (or foot!), they have a tong-like appearance which at first glance looks like two toes on each foot. This would give chameleons what is known as didactyl feet. Other didactyl species include sloths and many cloven-hoofed ungulates (hoofed mammals). However, upon closer inspection it becomes evident that there is more to each of these ‘toes’ than meets the eye… In fact, they are a bundle of toes fused together. On their front legs, the outer bundle has 3 toes and the inner has two. This is reversed on their back legs. The closest scientific description that we have at the moment is ‘zygodactyl’, which describes the feet of parrots and the majority of arboreal bird species. BUT, and here’s where it gets fascinating! They only have two toes on each side. The third chameleon toe in the different bundles removes them from fitting properly into that category. So there we have it. The lonely chameleon.

So why do chameleons have this cool, confusing adaptation? Scientists believe the enigmatic feet of these cold-blooded panthers are perfectly adapted for an arboreal lifestyle. The ‘tong-like’ formation of the toes allows the chameleon to wrap them around smaller branches and clasp tightly, providing excellent grip and stability. Each toe of the chameleon also has a small claw at the end. This claw allows them to walk along branches and climb trees that are too large for them to grip.

These arduous tasks are also greatly helped by their tail! The prehensile nature of the tail is another indication that panther chameleons have adapted to life in the trees. Prehensile tails are unique to animals that spend their lives in the tree canopy. Many ‘new world’ primate species, for example spider monkeys, possess a prehensile tail. Prehensile tails provide a couple of key benefits to our tree dwellers. Arguably the most useful benefit they provide is a point of anchorage, which the panther chameleon will use in many different situations. The tail is able to support the entire weight of the chameleon, allowing it to hang from branches (or roofs) and gain access to new parts of its habitat. When hunting, panther chameleons will wrap its tail around a tree for stability when using its weapon of choice… its projectile tongue. This anchorage is a necessity when you realise that the tongue can be as long as the chameleons body, and is ‘fired’ at prey from a distance!

As I watched Kobi trying to reach his goal, I got a look at just how well he was able to anchor himself (to the roof using his prehensile tail and tong-like feet). You’ll all be very relieved to hear that Kobi did in fact achieve his goal. Once he finally managed to clasp his front feet onto this small branch and lever himself into a stable position, he let go with his back legs and grabbed the branch with them. At this point he uncoiled his tail from the roof, and off he went in search of his next meal.

The panther Chameleon is one of the most common chameleon species in the North/north-west of Madagascar, and definitely one of the most versatile. Populations from different areas of the country display different arrays of colour. Contrary to, well every belief really, chameleons aren’t able to just change to any colour that they like. Thanks Pascal! All colour changing chameleons have a set palette. Most of the time their colour change isn’t a conscious choice, but a product of physiological necessity. So the colour range of Furcifer Pardalis is insane!

Or is it? A 2015 study by Grbic et al. has thrown significant doubt on the conservation status of the panther Chameleon. Prior to 2015, all of these locales were thought to be the same species: F.pardalis. Now it has been revealed that there is sufficient genetic and behavioural, behavioural being a significant lack of interbreeding between locales, evidence to suggest that what was initially thought to be only one species is actually eleven!

Furcifer pardalis is currently listed as ‘Least Concern’ by the IUCN, the International Union of Conservation for Nature. However, this classification is based on the idea that all locales are the same species. Each of these newly discovered Furcifer species will need to be individually assessedto decipher how threatened they really are. Only based on that information can management strategies be updated to ensure the ongoing health and survival of all 11 species of the panther chameleon.

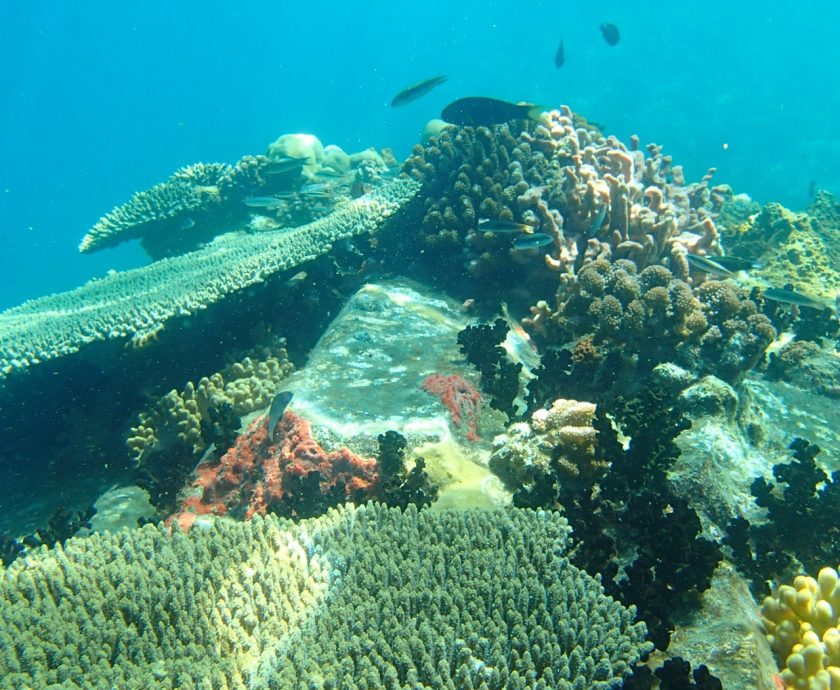

The panther chameleon, similar to most arboreal chameleons, prefers areas surrounding waterways; it generally struggles to survive in areas of dense forest. Instead they tend to spend most of their lives in more open areas, such as in trees that overhang streams, or, as has been identified on Nosy Be, overhanging roads. A study by Andreone et al 2005 espoused the importance of an area of buffer vegetation between roads and either forest or agricultural land, as it was in these areas that the panther chameleon was most commonly found. While being around roads presents other issues for slow-moving chameleons like Kobi, these findings suggest that a buffer zone between roads and panther habitat is an important management step for the ongoing survival of the panther.

Check out our Forest Conservation Program

Follow Angus’s Blog Here

References

1. Grbic, D., Saenko, S. V., Randriamoria, T. M., Debry, A., Raselimanana, A. P. and Milinkovitch, M. C. (2015), Phylogeography and support vector machine classification of colour variation in panther chameleons. Molecular Ecology.

2. : F. Andreone , F. M. Guarino & J. E. Randrianirina (2005) Life history traits, age profile, and conservation of the panther chameleon, Furcifer pardalis (Cuvier 1829), at Nosy Be, NW Madagascar, Tropical Zoology, 18:2, 209-225.